Bad Banks: The Chinese Piece for an Indian Jigsaw

Rishabh Luthra

What are Bad Loans and Non-Performing Assets? –

A bank’s assets are the loans and advances that it extends to its customers. If these clients, including companies, do not repay either interest, part of the principle, or both, the loan turns into a bad loan. Thus, bad loans are the one that has not been repaid within the stipulated time, or where the scheduled payments are in arrears for over 90 days. The banking industry refers to these bad loans as Non-Performing Assets (NPA).

The monetary watchdog, Reserve Bank of India (RBI) broadly defines a non-performing asset as “An asset, including a leased asset, becomes non-performing when it ceases to generate income for the bank”.

How do these NPA impact the Economy? –

Impact on Banks-

The main source of income for a bank is the interest received on loans given to the borrower. With that income, the bank pays interest to the depositors. The balance between the interest income and interest paid is the profit for the bank. Due to this reason, the interest charged by banks on borrowings is higher than what is provided on deposits.

Also, the deposits received by banks are used to extend loans to borrowers. And when loans are not repaid by the borrower, the bank would find it difficult to repay the deposits to its customers. So, it is imperative for the banks to recover loans along with their interest on time.

When a bank loses money via unpaid loans, it can compensate for it by either charging higher interest on subsequent loans, or by offering lower interest to its depositories. The problem aggravates when the bad loans increase to an amount which makes it impossible to be recouped by some tweaks in interest. To fix this, banks need to indefinitely overhaul their functioning and structures to permanently resolve the problem.

Impact on Companies-

Due to large NPAs banks increase their lending rates. This affects the balance sheet of the companies and their operations.

The rise in interest rates from banks leads to an increase in the borrowing cost of the companies ultimately leading to an increase in the liabilities of the company. This has an adverse effect on the image of the company to the outside world.

High interest leads to more part of profits acquainted with the interest repayment which leads to a decrease in the profit remaining for the shareholders. Thus, Shareholders’ equity decreases when the interest rates are increased by the banks.

When there is an increase in the NPA of banks in an economy, interest rates on both business and personal loans will go up. Borrowing money via credit cards, mortgages or auto loans will become more expensive. This curbs consumer spending on essentially all kinds of products and services, resulting in lower sales for most companies. This, too, will lead to lower profits, and consequently less shareholder equity on the balance sheet.

All these effects are cumulated through the rise in NPAs of the Banking sector leading to disruptions in the working of the economy.

Current Scenario of NPAs in India –

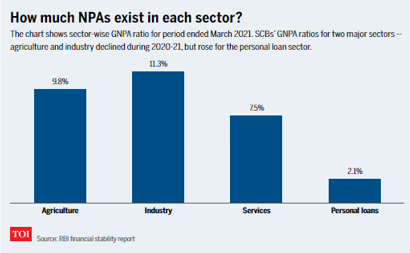

As of March 2021, the total bad loans in the banking system were estimated to be INR. 8.35 Lakh Crore

Comparison of NPA with global peers –

As per World Bank data, the share of NPA to gross loans in India is significantly higher compared to developed western economies. It also exceeds most emerging economies.

What are Bad Banks and how do they help the economy? –

Aforementioned, bad loans aren’t just bad, they are purely toxic. Once unpaid loans start piling up, the whole bank seems suspect. New investors won’t want to pour money into these institutions anymore. And even when they manage to borrow money from outside investors they’ll have to do it at such exorbitant interest rates, crippling them financially.

So, what can be done?

One solution for this is to move all the toxic loans elsewhere. This way, the bank will be left with the pristine stuff — the good loans (loans that are likely to be repaid in full) and they can focus on this stuff rather than worrying about the toxic loans.

Also, when outside investors look at the bank the next time around, they will see that there’s a real money-making opportunity here. No toxic stuff!!!

Question is, where to move this bad stuff?

We could move it to a bad bank that can resolve this stuff. So what is a bad bank??

A bad bank is a corporate entity that alienates illiquid and risky assets held by banks and financial institutions or a group of banks. It is created to help banks clear their balance sheets by transferring their bad loans so that the banks can focus on their core business of taking deposits and lending money.

Moreover in India, a large portion of NPAs are with the government-owned public sector banks (PSBs). In the past, the government had to infuse fresh capital to improve the financial health of PSBs. The government infusing fresh capital in PSB means less money for other schemes. Here comes a Bad Bank to the rescue. This corporation will take all the NPA’s from the banks at an agreed value which will clear all the toxic stuff from the balance sheet of the bank and provide a good picture of the bank to the outside investors. Then, this bad bank will work to solve this ‘bad stuff’ by selling the collateral of the loans and resolving the amount through debt collection. This way, all the toxic stuff of the economy could be transferred to one place and be managed by professionals to resolve these NPA’s and resupply it into the economy.

Bad Banks in the World –

The first-ever bank to use this bad banks strategy was Mellon Bank, which created a bad bank entity in 1988 to hold $1.4 billion of bad loans. The bad bank entity was named “Grant Street National Bank” (GSNB), to enter into a transaction to hold all of its bad assets with a book value of roughly USD 1 Billion. This improved the asset quality of Mellon bank and allowed its management to focus on its core business and return to profitability. The bad bank eventually repaid all its bondholders in three years. It was ultimately liquidated in 1995 after successfully realizing the bad assets and paying all of its obligations.

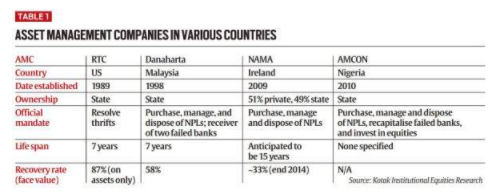

The table below shows the data on Asset Management Companies in Various Countries over the past years and their operations

India’s Policy towards the Bad Banks –

According to reports, the government wants to move roughly INR. 2.2 lakh crore worth of unpaid loans to this institution. In fact, they are not even calling it a bad bank. They are referring to it as a private entity that will adopt an ARC-AMC model for resolving stressed assets.

ARCs technically aren’t new. These Asset Reconstruction Companies (ARCs) buy unpaid loans from banks and try to resolve them. The government intends to set up a well-funded ARC that can buy bad loans in bulk from multiple banking institutions and aggregate them in one place. These institutions won’t pay the full amount in cash. Instead, they will put up 15% in cash and pay the rest via security deposits. This means the ARC will only pay the banks the remaining 85% when they actually recover the money.

The Asset Management Company (AMC) comes into the picture now. The current model will allow the ARC to transfer the loans to the AMCs who will ultimately be responsible for resolving them.

National Asset Reconstruction Company Limited (NARCL) has already been incorporated under the Companies Act. It will acquire stressed assets worth about INR. 2 lakh crore from various commercial banks in different phases. Another entity — India Debt Resolution Company Ltd (IDRCL), which has also been set up — will then try to sell the stressed assets in the market. The NARCL-IDRCL structure is the new bad bank. To make it work, the government has authorized the use of INR. 30,600 crore to be used as a guarantee.

The NARCL will first purchase bad loans from banks. It will pay 15% of the agreed price in cash and the remaining 85% will be in the form of “Security Receipts”. When the assets are sold, with the help of IDRCL, the commercial banks will be paid back the rest.

If the bad bank is unable to sell the bad loan or has to sell it at a loss, then the government guarantee will be invoked and the difference between what the commercial bank was supposed to get and what the bad bank was able to raise will be paid from the INR. 30,600 crore has been provided by the government.

Criticism over Bad Banks –

Most of these bad assets are already fully provided for, written down on the books of banks. The banks no longer nurture hopes of a meaningful recovery.

Another issue which may arise, is selling stressed assets to potential buyers and resolving the underlying crisis in the system. In the current situation, when economic conditions are highly volatile, finding potential buyers for distressed assets can be a significant challenge.

One challenge private sector ARCs face is that of capital. None of the entities till now has been allowed to tap the capital market for raising funds. Some central banks as well as government officials also admitted capital was the biggest challenge in setting up a ‘bad’ bank.

An undesirable outcome that the NARCL runs the risk of facing is that it may simply turn into a storage house for distressed assets after struggling to find takers for them. Care must be taken to avoid such an outcome as it would only exacerbate the problem in the long run.

Case study of Bad Banks in China –

China is struggling with one of its biggest bad banks, the China Huarong Asset Management Co. Ltd. (Huarong). The Hong Kong-listed company, which counts the Chinese government as a principal shareholder, recently stoked financial stability concerns when it passed over a potential bond default. Earlier this year, its former Chairman Lai Xiaomin was executed for soliciting bribes, corruption and bigamy. This experience forms an important example for India to continue with its strategy of Bad Bank.

In the aftermath of the Asian financial crisis, China set up dedicated bad banks for each of its big four state-owned commercial banks. These bad banks were meant to acquire non-performing loans (NPLs) from those banks and resolve them within 10 years.

In 2009, their tenure was extended indefinitely. In 2012, China permitted the establishment of one local bad bank per province. In 2016, two local bad banks were allowed per province. By the end of 2019, the country had 59 local bad banks.

Recent research highlights that Chinese bad banks effectively help conceal NPLs. The banks finance over 90 per cent of NPL transactions through direct loans to bad banks or indirect financing vehicles. The bad banks resell over 70 per cent of the NPLs at inflated prices to third parties, who happen to be borrowers of the same banks. The researchers conclude that in the presence of binding financial regulations and opaque market structures, the bad bank model could create perverse incentives to hide bad loans instead of resolving them.

Moving to Huarong, the main source of the problem appears to be the gradual broadening of the original scope and tenure of Chinese bad banks. Recently The Huarong transformed itself into an investment bank with a multitude of subsidiaries, doing everything from real estate and securities broking to insurance and high-yield cross-border lending. Many of its losses are thought to be linked to loans it made to companies that have since gone bust.

Lessons to be learnt from china –

The Chinese experience holds three major lessons for India.

First, a centralised bad bank like NARCL should ideally have a finite tenure. Such an institution is typically a swift response to an abrupt economic shock (like Covid-19) when orderly disposal of bad loans via direct sales may not be possible. The banks could transfer their crisis-induced NPAs to the bad bank and focus on expanding lending activity. Over time, it could gradually dispose of the assets to private players, thus avoiding a fire-sale during the economic shock. Clearly, such a bad bank has a temporary purpose, and need not exist in perpetuity.

Second, a bad bank must have a specific, narrow scope with clearly defined goals. Transferring NPAs to a bad bank is not a solution in itself. There must be a clear resolution strategy. Otherwise, allowing a bad bank to exist in perpetuity threatens the financial stability of the country. The Huarong failure is a case in point.

Third, in a steady-state, the resolution of bad loans should happen through a market mechanism and not through a multitude of bad banks to ensure the supply of money into the economy and not circulation among different bad banks which provides a fake picture of money supply in the economy.

The Chinese experience with Bad Banks and the Huarong failure provides a wide narrative to India to form its policy accordingly and prevent such failures in the country itself in the future.

Conclusion –

The overall research concludes that the policy of bad banks in the Indian context is an impressive policy to tackle the increase of NPAs in the economy. The proposal being tossed around for seven years was revived in 2020 and announced in the budget for the years 2021-22. In the recent announcements by the Ministry of Finance, the proposal of these bad banks has been cleared and they are all set to go into action this year. However, before continuing with the structuring and working of bad banks, the GOI needs to ensure that these institutions don’t end up like China’s bad bank structure. Also, the government needs to provide due diligence to the challenges that this bad bank is likely to face in its implementation. If proved to be successful, this initiative of the government can significantly reduce the NPAs of Indian Banks and increase the efficiency of the Indian economy.

Edited by Shon Kipgen

Citations

- “Budget and Bad Banks.” Finshots, 5 Feb. 2021 , https://finshots.in/markets/budget-and-bad-banks/.

- “Bad Bank.” Wikipedia, Wikimedia Foundation, 16 Feb. 2022, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bad_bank

- Team, MintGenie. “What Is a Bad Bank? What Are NPAS? How Do They Impact the Banking Sector?” Mint, 27 Sept. 2021, https://www.livemint.com/industry/banking/what-is-a-bad-bank-what-are-npas-how-do-they-impact-the-banking-sector-and-the-interest-rates-11632746628980.html.

- Misra, Udit. “Explained: What Is Good about a ‘Bad Bank’.” The Indian Express, 18 Sept. 2021, https://indianexpress.com/article/explained/explained-whats-good-about-a-bad-bank-7513911/.

- Punj, Shwweta. “How ‘Bad Banks’ Offer the Indian Economy a Fresh Start.” India Today, 26 Sept. 2021, https://www.indiatoday.in/india-today-insight/story/how-bad-banks-offer-the-indian-economy-a-fresh-start-1857470-2021-09-26

TIMESOFINDIA.COM / Updated: Sep 17, 2021. “Explained: Why India Needed a Bad Bank – Times of India.” The Times of India, TOI, https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/business/india-business/explained-why-a-bad-bank-is-needed-in-india/articleshow/86269329.cms